Blessed Bartolo Longo (1841-1926) was beatified by St. John Paul II on 26th October 1980. Pope Benedict XVI, speaking of Bartolo Longo in a homily, likened him to St Paul of Tarsus, who also initially persecuted the Church and described Bartolo as being "militantly anticlerical and engaging in spiritualist and superstitious practices". His story is quite amazing. Born into a devoutly Catholic family in the small town of Latiano in Brindisi, southern Italy, Bartolo grew up in a home where his parents, Bartolomeo and Antonina prayed the rosary together daily. However when Bartolo was just 10 years old, his mother died and he slowly drifted away from the faith. Studying Law at university in Naples he became involved with an occult sect and was “ordained” as a satanic “priest”. He took part in séances, fortune telling and orgies and began to publicly ridicule Christianity encouraging other Catholics to leave the Church. None of these activities brought him any joy and his personal life was marked by extreme depression, paranoia, confusion and anxiety. He ultimately experienced a complete mental breakdown. In the depths of despair, Bartolo heard the voice of his deceased father urging him to “return to God, return to God”. He turned to a friend for help, who convinced him to abandon Satan and seek the help of a Dominican priest, Fr Alberto Radente. Bartolo made a full confession and Fr Radente further helped him to reclaim his life.

One evening, as he walked near-the ruins of a chapel in Pompeii, Bartolo had a profound mystical experience. He wrote: "As I pondered over my condition, I experienced a deep sense of despair and almost committed suicide. Then I heard an echo in my ear of the voice of Friar Alberto repeating the words of the Blessed Virgin Mary: ‘If you seek salvation, promulgate the rosary. This is Mary's own promise’. These words illumined my soul. I went on my knees. 'If it is true. I will not leave this valley until I have propagated your rosary.' Bartolo became a Third Order Dominican, taking the name Brother Rosario in honour of the rosary and joined a charitable group in Pompeii. He worked alongside Countess Mariana di Fusco, a wealthy local widow whom he later married.The couple decided to start a confraternity of the rosary. To serve as a spiritual focus for this group, Bartolo needed a painting of the Blessed Virgin and was offered one by Sister Maria Concetta de Litala of the Monastery of the Rosary at Porta Medina. She had found it in a second hand shop in Naples and had paid a tiny amount of money for it. Though it was not considered of particular aesthetic beauty and was in very poor condition, it served Bartolo's purpose. He described it in his journal: "Not only was it worm-eaten, but the face of the Madonna was that of a coarse, rough country-woman, a piece of canvas was missing just above her head, her mantle was cracked. Nothing need be said of the hideousness of the other figures. St Dominic looked like a street idiot. To Our Lady's left was a St Rose. This I had changed later into a St Catherine of Siena . I hesitated whether to refuse the gift or to accept, I took it."

In addition, Bartolo restored a ruined church in Pompeii in October 1873 and then sponsored a feast in honour of Our Lady of the rosary. He installed the repaired painting in this very church. Within hours of its installation miracles began to be reported and people came to the church in droves. Seeing the devotion of the pilgrims, the Bishop of Nola encouraged Bartolo to construct a larger church. He approached the architect Giovanni Rispoli to build it, making the following appeal: "In this place selected for its prodigies, we wish to leave to present and future generations a monument to the Queen of Victories that will be less unworthy of her greatness but more worthy of our faith and love." Bartolo continued promoting the rosary and spreading devotion to Our Lady until his death in 1926, at the age of 75. He would evangelise young people at parties and in local cafes, explaining the dangers of occultism. He would witness continually as to the glories of Christ, the munificence of His mother and the beauty of the Catholic Faith.

0 Comments

St Louis Marie was born in Brittany in 1673. He studied in Paris and was ordained to the priesthood in 1700. He died at the age of 43 years in St Laurent sur Sevres, after a life as an itinerant preacher, devoted to the poor and to preaching against the errors of Jansenism, which did not make him popular with some of the bishops of his time. Pope Clement XI conferred on him the title and authority of Missionary Apostolic, confirming him in his mission . As a student, he took great delight in researching the writings of the Church Fathers, Doctors and Saints as they related to the Blessed Virgin Mary, to whom he was singularly devoted. Under her inspiration, he founded the Daughters of Divine Wisdom, who were committed to the care of the destitute and in 1715, a year before his death, founded a missionary band known as the Company or Mary. A member of the Third Order of St Dominic, he was one of the greatest apostles of the Rosary in his day, promoting authentic Marian devotion wherever he went. His greatest contribution to the Church and the world is Total Consecration to the Blessed Virgin. Among his most influential writings were: The Secret of Mary, The Secret of the Rosary, True Devotion to Mary which has influenced countless people since, including Pope John Paul II, Frank Duff, founder of the Legion of Mary and Matt Talbot, to name but a few. The cause for his declaration as a Doctor of the Church is now being pursued. Although St Louis is perhaps best known for his Mariology and devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary, his spirituality is founded on the mystery of the Incarnation of Jesus Christ, and is centred on Christ. Hail, then, O immaculate Mary,

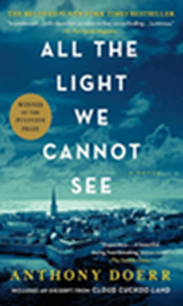

living tabernacle of the Divinity, where the Eternal Wisdom willed to be hidden and to be adored by angels and by men! Hail, O Queen of Heaven and earth, to whose empire everything is subject which is under God. Hail, O sure refuge of sinners, whose mercy fails no one. Hear the desires which I have of the Divine Wisdom; and for that end receive the vows and offerings which in my lowliness I present to thee. St Louis Marie, from “True Devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary” all the light we cannot see, by Anthony Doerr The title caught my attention. “All the Light we cannot see” immediately set me thinking of the mystery of God. I knew that the drama series was not going to explicitly approach the mystery of God. Nevertheless, I wondered if anything of what the title evoked for me was to be found in the programme. I decided to take a look. I wasn’t disappointed. This is a short, four-part drama series, recently released in November 2023 currently streaming on Netflix which is based on the The Puliter Prize winning novel of the same name by Anthony Doerr (2014). The story unfolds in the context of World War II, mainly in Occupied France. The two characters we follow most closely are Marie-Laure LeBlanc who is a young French teenager who is blind, and Werner Pfenning who is a German youth serving in Hitler’s Nazi army. Their paths finally cross in the French port of St Malo, at the end of the War. We won’t spoil it for you by saying too much! However, some reflections that might accompany your viewing, concern how Truth and beauty are attributes of God and following on from this the whole of creation is marked by truth and beauty, points to God and communicates something of God. The human spirit is consoled, strengthened and ennobled by truth and can better withstand the onslaught of evil and destruction when it has been formed and tasted truth. Worth watching! We often use language associated with light in order to say something about God. Making a connection between God and light in this way has of course a firm basis in Scripture. The Book of Genesis tells the story of creation and how God created all that is, created light, separated light from darkness, modulated the rhythms of day with night, and the unfolding of seasons. In the New Testament the theme of light is especially developed in the Gospel of St John - which notably "God is light, in him there is no darkness at all". Jesus is "The Light of the World", those who follow Him "walk in the light" (cf. also Is.). Mystics and theologians throughout the centuries have endeavoured to speak of God and have taken up the language of light. God is so knowable, infinitely knowable – no matter how close we come to God, how much we know Him, we could never as it were exhaust the mystery of God. Trish 1/2/2024 book review - conscience before conformity: Hans and Sophie Scholl and The White Rose resistance in Nazi Germany, by paul shrimptonRead NowConscience before Conformity: Hans and Sophie Scholl and The White Rose resistance in Nazi Germany, by Paul Shrimpton (Gracewing). In the midst of Nazi oppression a few young German students had the freedom of thought and courage to speak the truth. They took the name of The White Rose - and with the limited means available to them, especially through printed leaflets, they opposed Hitler and the Third Reich and called on others to offer peaceful determined resistance to the spread of Nazism. Hans and Sophie Scholl along with Christoph Probst were tried and executed by the Nazis in Munich in1943. The story of Hans and Sophie Scholl who were the inspiration and leaders of The White Rose movement has been told many times. However, prior to this book by Paul Shrimpton it seems that a critical aspect had been ignored. No-one had spoken about the reality that Christian faith undergirded and fuelled their daring endeavour: the students and most of those who influenced them were Christians and in particular Catholic. Here at last Shrimpton rectifies this omission. We are introduced to their journey: how they discovered and drank deeply from the thought of great Christian writers such as St Augustine, St Thomas Aquinas, Pascal and St John Henry Newman. These young people changed radically: from being actively involved in the Hitler Youth they stepped out, took up the countercultural dangerous path of resistance to Nazism. Newman and his ‘theology of conscience’ had a remarkable effect on the students and on Sophie in particular. Her conscience was awoken, she regained her freedom and the necessary assurance and courage to resist the draw of evil and live. The White Rose printed leaflets with which they set forth their ideas and denounced Nazism. We might wonder at the power of words: how reading Newman opened a new path for these young people; how the Nazis searched out and tried to silence the authors of these pamphlets. We can learn from the story of The White Rose, draw inspiration from them in our times when we too must choose between conscience and conformity. Then and now, their words speak out and bring hope. Certainly this book is worth reading. Trish A DEFINITION OF 'PARABLE' Nathan Reproaches David, Englebert Fisen (1655 - 1733) Nathan Reproaches David, Englebert Fisen (1655 - 1733) The Greek root of the term translated into English as ‘parable’ παραβολή is found in ‘παρα’ meaning ‘close beside’ or ‘with’ and the verb ‘βάλλω’ ‘I cast’. It means a juxtaposition or comparison and appears already in the 4th century BC writings of Plato[1] and Aristotle[2]. In the New Testament, parable is considered to be a teaching aid, cast alongside the truth being taught for the sake of comparison. Much has been made of the Greek cultural influence on the Gospel writers, sometimes at the expense of the Semitic influence. In the Septuagint, παραβολή is also used to translate the Hebrew term מָשָׁל transliterated as ‘mashal’. The noun has a more wide-ranging meaning than we would typically associate with the word ‘parable’ as we understand it in English and is used around forty times in the Old Testament, having been translated as ‘argument’ (Job 27:1; 29:1), ‘oracle’ (Nb 23:7, 18; Hab: 2:6), ‘byword’, ‘discourse’, ‘parable’ (Ezek 17:2) ‘proverb’ (1 Sam 10:12) ‘taunt’ (Is 14:4). However, when examined, it appears to represent a much broader category of literary devices, including: simile, fable, riddle, allegory, symbol, example and theme. The parable can be a simile developed and expanded into a story. The Hebrew also has a verbal form משׁל, which means to ‘represent’ or ‘be like’. The verb denominative can mean to ‘use a proverb’, ‘speak in parables or sentences of poetry’. The latter is most common in the prophet Ezekiel (12:23; 17:2; 24:3; 17:3 for example). The uses of מָשָׁל will be considered in the next section. This accounts for how, when used in the New Testament ‘parable’ is at times a very loose and general term, as the use of it in Lk 6:39-42 demonstrates. The parables of Jesus share some common traits: the story is made up of basic components that are true to life, although the story itself may be fictitious. The similes used are commonly agricultural regarding seeds and sowing for example or concerned with fishing, but also coins, leaven, lamps are frequently mentioned. An overall message is generally communicated through the story, with any extra details at the service of the main message. PARABLES IN THE OLD TESTAMENT It was while researching the whole area of parables in the Bible in preparation for a dissertation on The Good Samaritan, that I came across the notion of ‘parable’ in the Old Testament. The Old Testament is brimming with metaphorical language and unforgettable imagery. The Jews had many apothegms and perceptive witty sayings, not to mention the Wisdom writings and in particular the Book of Proverbs. Some of the parables told by Jesus can be recognised in familiar Old Testament ones with the new reality of the Kingdom of God set in their heart. The parable of the Wicked Husbandmen, recounted by all three synoptic gospels (Mt 21: 33-46; Mk 12: 1-12; Lk 20:9-19), finds an Old Testament echo in Isaiah 5:1-7, as does the parable of the Mustard Seed (Mt 13:31-32; Mk 4:30-32; Lk 13:18-19) in Ezekiel 17:1-24. But perhaps those stories in the Old Testament that conform most closely to the New Testament version of ‘parable’ as illustrated in the Good Samaritan, even though they are sometimes not actually associated with the word מָשָׁל mashal, are the narratives of the Poor Man’s Ewe Lamb (2 S 12:1-4), the Tekoan Woman (2 S 14:4), the Lost Prisoner (1 K 20:38-42), the Vineyard (Is 5:1-7) and the Ploughman (Is 28:23-29). The Old Testament parables were frequently a tool in the hands of the Prophets, serving as a reminder of God’s Covenant and the Law and they provide some indications of both the moral and social aspects of life in the history and journey of God’s people. The Poor Man’s Ewe Lamb, in 2 Samuel (12:1-4), which continues to have its place in the Lectionary[3], demonstrates very clearly the power of parabolic speech. However, not all scholars agreed about its classification as a ‘parable’. Hermann Gunkel, the influential German Old Testament scholar and founder of form criticism, argued that “it affords no parallel at all to the situation to which it is applied” and consigned it to the stock of ‘fairy tales’ as it did not seem to belong to the context.[4] The parable itself is made up of only four verses and is spoken by the prophet Nathan. It is concise and to the point and stirs up in any heart a sense of anger at the injustice served by the rich man and a deep sense of sympathy and compassion for the poor man, whose cherished and only ewe lamb is seized needlessly by the rich man to furnish his table upon the arrival of a ‘stranger’. It is an extraordinary accomplishment in such a few words and the effect it had on David, who recognised in it the utterly despicable nature of his adultery and murderous crime, was just as striking. The story exemplifies the notion of juxtaposition or casting something alongside the truth being taught for the sake of comparison, that we have come to recognise as ‘parable’. It is the Lord who communicates in this way with David through the intermediary of the prophet Nathan because “the thing that David had done displeased the Lord” (2 S 11:27). By a careful selection of words, Nathan, who has the very difficult task of communicating God’s displeasure to David, leads the king to unsuspectingly pronounce judgment on his own deeds. “You are the man”, Nathan reveals the truth to David (2 S 12:7). In a similar way, the parable of the wicked tenants (husbandmen) (Mt 21:33-45) causes Jesus’ hearers to pronounce judgement on themselves without being aware of it, through the insertion of λέγουσιν αὐτῷ in Mt 21:41. This is also the case in the parable of the Two Sons (Mt 21:31) and in the Sinful Woman forgiven (Lk 7:43).[5] The parable has been described in different ways: Simon categorises it as a ’juridical parable’ in that it “constitutes a realistic story about a violation of the law, related to someone who had committed a similar offence with the purpose of leading the unsuspecting hearer to pass judgment on himself”.[6] For MacDougall, it is a ‘parable of fact’ as opposed to one of ‘fable’ or ‘fancy’[7] although Von Rad regarded it as a ‘fable’ of which many are applied in a political context. “In the fable, there occurs a veiling of something everyday, a kind of alienation in the direction of the unreal and the fabulous. But precisely in this strange dress the truth is more forceful than in the everyday where it is so easily overlooked”[8] In MacDougall’s estimation, the Old Testament parables provided the “scheme, the system, the power and the genius of parabolic teaching.”[9] [1] BURNET, J., Platonis opera, vol. 2. ΣΩ. Ἐρρήθη γάρ που τότε ἐν τῇ παραβολῇ τῶν βίων μηδὲν δεῖν μήτε μέγα μήτε σμικρὸν χαίρειν τῷ τὸν τοῦ νοεῖν καὶ φρονεῖν βίον ἑλομένῳ. soc. Yes, for it was said, you know, in our comparison of the lives that he who chose the life of mind and wisdom was to have no feeling of pleasure, great or small. [2] ROSS, W.D. Aristotelis ars rhetorica [3] The parable of the Poor Man’s Ewe lamb continues to form a part of the Catholic Lectionary and is read on Saturday of Week 3 of Ordinary Time (Cycle II) including David’s penitence (2 S 12:1-7, 10-17). The gospel reading is Mk 4:35-41, the calming of the storm. The psalm is 50: A pure heart create for me O God. [4] SIMON, Uriel. “The Poor Man’s Ewe-Lamb, An Example of a Juridical Parable” p.220 [5] Cf. JEREMIAS, J. The Parables of Jesus, p.28 [6] SIMON, Uriel. “The Poor Man’s Ewe-Lamb, An Example of a Juridical Parable”, pp. 220-221 [7] MacDOUGALL, John. The Old Testament Parables, pp. 9-10. [8] VON RAD, G. Wisdom in Israel, p.42 [9] MacDOUGALL, John. The Old Testament Parables, pp. 9-10. REFERENCES

BURNET, J. Platonis opera, vol. 2, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1901 (repr. 1967): St II.11a-67b. [Online: http://stephanus.tlg.uci.edu/Iris/Cite?0059:010:55521] JEREMIAS, Joachim. The Parables of Jesus, (3rd Revised Edition). London: SCM Press Ltd, 1972 Translation based on that of: S.H. Hooke from German Die Gleichnisse Jesu, 6th edition published 1962 by Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Gottingen. Revised Edition. Chatham: W. & M. Mackay & Co. Ltd, 1963. MACDOUGALL, John. The Old Testament Parables. London: James Clarke and Company, 1934. ROSS, W.D. Aristotelis ars rhetorica, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1959 (repr. 1964): 1-191 (1354a1-1420a8). [Online: http://stephanus.tlg.uci.edu/Iris/Cite?0086:038:326191] SIMON, Uriel. “The Poor Man’s Ewe-Lamb, An Example of a Juridical Parable” Biblica, 1967, Vol 48, No. 2 pp.207-242. [Online https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/23488221.pdf?ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_gSIMON, Uriel. VON RAD, Gerhard. Wisdom in Israel. First published in German under title Weisheit in Israel, Neukirchen-Vluyn, 1970. English translation James D. Martin. London: SCM Press Ltd., 1993.  In 1917 when the world was reeling from the First World War, Our Blessed Mother chose three little children in Portugal to bring a message of peace to the world, a promise of peace, if we changed our ways and turned to God. She came to ask us to pray the Rosary, to make sacrifices for sinners, to do the Five First Saturdays. Jacinta (6yrs), Francesco (8yrs) Lucia (9yrs) to whom Our Blessed Mother appeared, understood this message and embraced it with all their little hearts, although still so young. I recently visited Fatima where these events took place and was deeply touched by the lives of these children. No sacrifice was too great for them, even to giving their lunch away and fasting from food and drink all day to do penance for poor sinners. They refused to be forced to tell a lie about the apparitions even when threatened to be put in boiling oil. Their love of the rosary was immense and they never wasted a moment when they could pray the rosary for the needs of Our Blessed Mother and those of the world. They are truly an example that can be held up for children of their age and indeed for us. In our very troubled world today where violence and war are escalating and suffering for so many is extreme, Our Lady is again inviting children to pray the Rosary. Many small children’s prayer groups are springing up all over the world, part of a movement called The Children’s Rosary, where it is the children themselves who lead and say the rosary and pray for peace in our world. These Rosary groups are like pure incandescent lights in the darkness of the world. There are many beautiful testimonies from the children who love to pray the rosary and get great solace from the presence of Our Lady. One little girl said that she loves to continue saying the rosary throughout the day at home such is the great comfort she receives from reciting it! In thinking about children’s prayers I’m reminded of what Our Lord said about the children “Take care that you do not despise one of these little ones; for, I tell you, in heaven their angels continually see the face of my Father in Heaven.” (Matthew 18:10) That is truly a beautiful thought. In another instance Jesus says to the Pharisees who judged the children’s cries of Hosanna inappropriate “Out of the mouths of infants and nursing babies you have prepared praise for yourself’” (Matthew 21:16) Their purity, their direct contact with God, their innate ability to see the world with untarnished eyes and approach it with boundless compassion makes their prayers powerful over the Heart of God. How important it is for our children today to learn to have a relationship with Jesus and Our Blessed Mother if they are to steer their way through all the venomous elements the world is going to propose to them, at school, and among peers. A faith that is purely based on ritual no longer holds firm with the winds of secularism. This is one of the reasons we started a Sunday School in the Claddagh this year. Not only to teach children about their faith, but also to encourage them to get to know and have a relationship with God, Our Blessed Mother, their guardian angel etc. The sessions are based on the Word of God and the children discover how God’s Word is “alive and active” and can tell them something for their own lives. The other day in the Sunday School we decided to start our sessions with a decade of the rosary led by the children themselves. This brings a whole other dimension into our session, the Presence of Our Blessed Mother who can help them to understand and integrate the teachings and who, in doing so, brings them to Jesus her Son. I’d just like to end with the story of Rosa, a little girl in Colombia who was born deaf and dumb in the 18th Century. She was healed miraculously by Our Lady and as though to prove her miraculous visit to the doubting villagers a wonderful image of Mary carrying Jesus and giving the rosary to St Dominic appeared on the wall of a cave nearby. The colours could not be explained by scientists especially as they run deep into the cave’s wall for several meters. It was as though then and as she does today Mary is inviting us to take up the rosary like the little children, to pray for our world, to penetrate the hardest of hearts to bring them back to God. Kate

We have St Luke's Gospel to thank for those extraordinary details of Mary’s life, and the wonderful tenderness of the Nativity. St Luke is also known for his parables, of which at least fifteen are unique to his gospel. These parables are part of the reason Luke’s gospel is often referred to as the ‘Gospel of mercy’ or that in the collect for the Mass on his feast day, the Church refers to him as the saint who reveals “by his preaching and writings the mystery of [God’s] love for the poor”. The parable of The Good Samaritan (Lk 10:25-37) belongs to that Lucan tradition and it is proclaimed on the 15th Sunday of Ordinary Time in Year C of the liturgical calender. It expresses a deeply Christian truth, but has a universal human appeal. The person who is a ‘neighbour’ cannot indifferently pass by the suffering of another and the association of this vivid parable with basic human solidarity has meant that it has even been adopted by name into civil laws designed to ‘oblige’ Samaritan-like behaviour in countries that are not of the Judaeo-Christian tradition. The Good Samaritan has been a constant in the minds of Christians throughout Church history. It is represented in the illuminations of the 6th century Rossano Gospels and was one of the four most popular subjects depicted in 13th century French cathedrals. Used by St Pope Paul VI to sum up the pastoral attitude of the Second Vatican Council Fathers, the parable has figured prominently in the writings of each post-Conciliar Pope not least in its application to ‘health care’ for which it has a particular relevance. Pope St John Paul II declared it to be the parable that “best articulates the heart of the health care mission and ministry of Jesus Christ.” Most recently, it has been applied to “the care of persons in the critical and terminal phases of life” in the document Samaritanus Bonus (SB, 2020), published by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF). This document responds of course to arguments raised in support of euthanasia, but invites us also to consider the Gospel account more deeply. In Luke’s text, we hear that the Samaritan is “moved with compassion” when he “sees” the man who has fallen prey to the brigands. The Greek verb used by Luke ἐσπλαγχνίσθη implies a very visceral or deep seated reaction. The corresponding noun σπλάγχνα can refer to the gut, the intestines or even the womb. His pity is instantaneous and his ‘seeing’ produces a very different response to that of the first two passers-by. Up to this point in his Gospel, Luke has only used this word to describe Jesus’ reaction to the widow of Nain who has lost her son (7:13) and this is just one of three action verbs linking the parable to that one. Both Jesus at Nain and the Samaritan in the parable “see” the problem, “are moved with compassion” and “approach” the dead or half-dead individual. Thus, the model behaviour of the Samaritan has, for Luke, already and only ever been demonstrated by Jesus himself. Luke uses the verb once more in the parable of The Prodigal Son to describe the father’s compassionate response (15:20). The Samaritan’s compassion is manifested in the series of actions by which he cares for the man. He uses the resources he has available (oil and wine and his own animal), including his own money (two silver coins – i.e., two days’ wages). He gives of his own time (the next day). He gets other people to help (the innkeeper). He promises to follow up (on my way back). It is interesting that we never hear the outcome—did the man survive or did he eventually succumb to his injuries? This is not considered by Luke to be a necessary detail. Remarking the contrasting attitudes of the Priest, Levite and Samaritan when they “see” the man in need of help, Benedict XVI characterises the program of the Good Samaritan as “a heart that sees” (Deus Caritas Est, DCE 31b), a theme taken up in SB and by Pope Francis in Fratelli tutti. SB views this quality as “central to the program of the Good Samaritan” and linked to a compassionate heart which is touched and then engaged. The Samaritan stops to show care. He sees where love is needed and acts accordingly (DCE 31). He recognises in weakness God’s call to appreciate the place of human life as the primary common good of society. It is a sacred and inviolable gift and is the basis for the enjoyment of all other goods, including man’s transcendent vocation to a unique relationship with the Giver of life (Evangelium Vitae, EV 49). In Part III which is dedicated to the ‘seeing heart’, SB indicates the source of man’s original dignity as that which comes from being created in the image of God with the calling to exist in “the image and glory of God” (1 Cor 11:7; 2 Cor 3:18). Often a ‘loss of dignity’ is cited as a justification for euthanasia, but this could perhaps be better expressed as loss of a ‘sense of dignity’ or ‘self-worth’, which is not the same. Both John Paul II (Veritatis Splendor, VS 14) and Benedict XVI make the link between the Lucan parable and the Last Judgement (Mt 25: 31-46), which demonstrates that love becomes “the criterion for the definitive decision about a human life’s worth”. Jesus identifies himself with those in need (Mt 25:40) whereby “love of God and love of neighbour have become one: in the least of the brethren we find Jesus himself, and in Jesus we find God” (DCE 14). The “wine of hope” which was spoken of by St Augustine in his commentary on the parable is deemed by Benedict XVI to be the specific contribution of the Christian faith in the care of the sick and refers to the way in which God overcomes evil in the world. Pope Benedict XVI comments that “a society unable to accept the suffering of its members and incapable of helping to share their suffering, and to bear it inwardly through ‘compassion’ is a cruel and inhumane society” (Spe Salvi, SS 38). SB states that one of the greatest miseries and most profound sufferings in terminal illness consists in the loss of hope in the face of death. This hope is a fruit of the Paschal Mystery of Christ, who conquers sin and death and is proclaimed by the Christian witness. The Good Samaritan puts the face of his brother in difficulty at the centre of his heart, and sees his need, offers him whatever is required to repair his wound of desolation and to open his heart to the luminous beams of hope (SB). SB concludes that the mystery of the Redemption of the human person is in an astonishing way rooted in the loving involvement of God with human suffering, which is what the parable of The Good Samaritan communicates to us. Even within a “throwaway culture” Christian witness demonstrates that hope is always possible. Anne  The birth of Jesus in Bethlehem is the most awe-inspiring, glorious event in history. Christians recognise and celebrate this as the central event of history. However, what can sometimes go unnoticed is how Jesus’ coming was announced and prepared for throughout the ages: God in his loving kindness never abandoned his creation and humankind. Instead, God cared for them, progressively taught and led them in such a way as to prepare them for his coming “in the fullness of time”. In the unfolding of the story there are great characters and perennial lessons to be learnt. Some figures and scenes are especially familiar to us – but whether or not we are familiar with the general thrust of the storyline, these accounts deserve to be looked at more closely and pondered. The story of Joseph is forever vivid in our minds, closely associated with his coat of many colours. Joseph is rejected and mistreated by his brothers, sold into slavery and taken off to Egypt. Amongst the many lessons, we are shown the path of forgiveness and the providential care of God – nothing is impossible to him, everything can be taken up and brought to bear fruit. The account in Genesis develops many stages, which lead to a situation where the brothers, driven by famine, come in search of grain to Egypt and the house of Pharoah. With great drama, the saga culminates in Joseph revealing himself and forgiving his siblings. Furthermore, Joseph declares that although his brothers had intended to harm him, God intended to bring good from the situation and to save many (Genesis 45:5). Joseph’s stunning declaration can encourage us in our own lives.  The story of course foreshadows the great story of redemption: the saving work of Jesus. For us today, we can be encouraged and strengthened in hope: nothing is beyond the reach of grace. We may see the signs of brokenness and woundedness in ourselves and others; we may be confronted with difficult situations. However, we can always have hope, and place our trust in the Lord and ask for his grace, take the step and do what is ours to do. The story of Joseph, and how it fits within the greater plan of salvation is one which can be a source of great encouragement for us today. Some two thousand years later, we commemorate how that story of salvation unfolded and led to the birth of Our Lord. We recall with wonder and gratitude how Jesus was born to his mother Mary, in Bethlehem. But, not only do we cast our minds back and remember that past event. Today, as Christians, we are called to recognise that Jesus came and also to dare to claim that He had future generations in mind. He is not some impersonal saviour of the masses: Jesus came for me, for you. He awaits and indeed longs for each one of us to know his saving love and welcome him with trust. Trish Images: [Top Right] Giovanni Andrea de Ferrari 'Joseph's Coat Brought to Jacob', oil on canvas, c. 1640. [Bottom Right] Bl. Fra Angelico. Christ in Judgement (detail from the vault, Orvieto Cathedral)  The Promised Land which was a focus for Israel’s journey out of slavery to freedom was described as “A land flowing with milk and honey” (Exodus 3:8). The words are laden with a dynamic sense of well being and plenty. When we hear this description today, milk and honey might not appeal to us too much, but we know that the meaning is that what the Lord wants for us involves abundance; the life he invites us to share is indeed good, he came that we might have “life to the full” (John 10:10). I’m talking about honey and bees and the things of bees because I’ve started beekeeping. The hive arrived in May and I can safely say that it has been an uninterrupted series of learning experiences since then. Who could imagine that so much could be going on in the little world that is a hive! There’s always a surprise, something unexpected at each of the regular inspections (in summertime... not now that winter has set in!) It reminds me of getting a present as a child...the jolt of surprise at the unexpected, the unimaginable - which is delightful! What a marvel it is too to see the way the colony works with a common purpose - each bee doing their bit, carrying out their task, each tiny drop of nectar combining to make the store of honey, the phenomenal detail of the wax comb which holds the honey. The beauty and marvel of creation shines out in a wonderful way in this little world of bees and it’s a joy to get a glimpse of it! The honey too is delicious - it isn’t for nothing that the Land to be reached was described as “a land flowing with milk and honey”. Trish. |

Details

Archives |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed